Dante, misery, coincidences

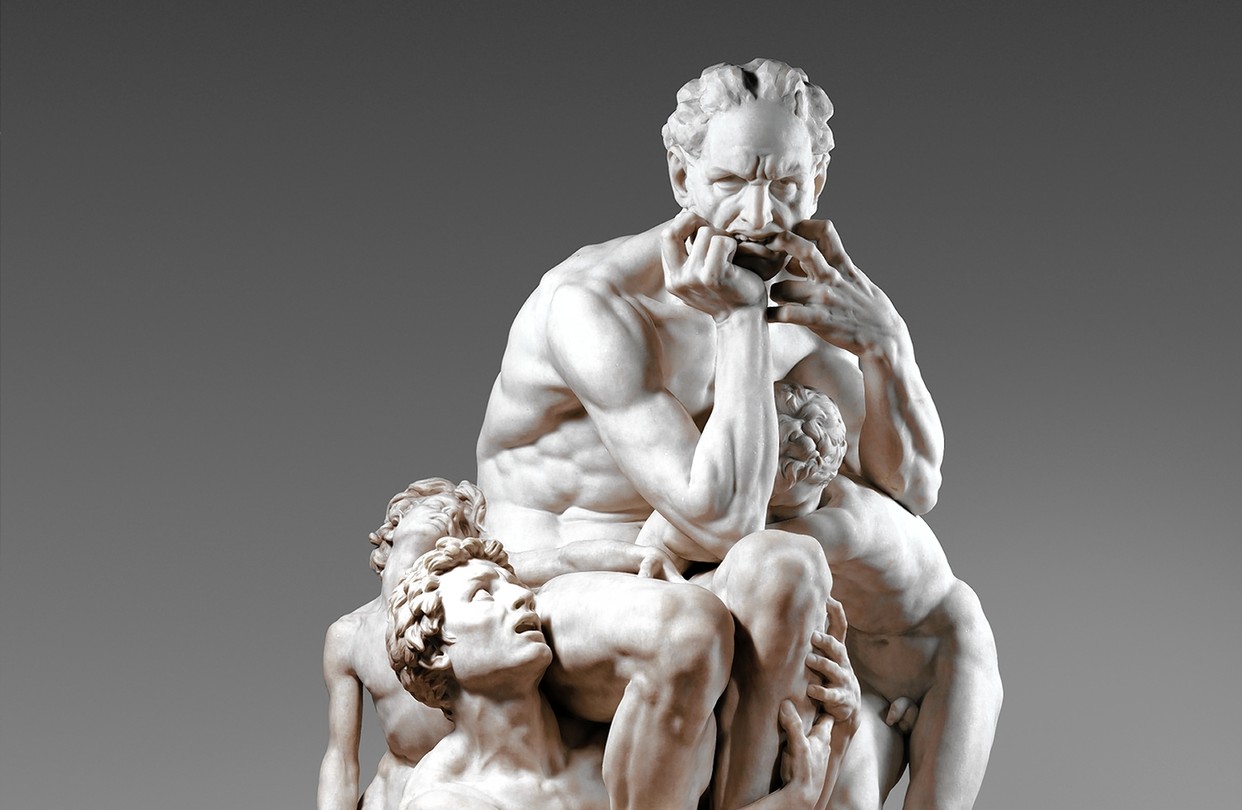

At my latest visit to the Met I was really struck by the intensity of the sculpture titled Ugolino and his Sons. It is inspired by the character Ugolino in Dante’s Inferno (which in turn was inspired by a real man in 13th century Italy), who is found guilty for treason and betrayal, and imprisoned with his sons and grandsons and left to starve. The placard describing the work takes it a step farther, positing that Ugolino had to decide between starvation and cannibalism — upon looking into this further, I learned that particular angle came from Dante himself.

Dante’s Inferno has been particularly relevant to me lately because this same week, I also signed on to an RA position where we are working on an exploratory project about that very same poem. I’ve been trying to explore creative ways to think about Dante’s work and the underlying themes in these verses, so randomly being drawn to this sculpture was a serendipitous moment.

What impacted me most about this sculpture is how Ugolino is depicted with such profound consternation and misery. Then I realized so many of the other sculptures I was drawn to were similarly grief-stricken in some way. The other most striking sculpture to me was titled The Martyr, depicting a woman lying in a precarious position, almost as if her body was flung there. From the Met’s website,

Rodin depicts the young woman posed in an attitude of death: her supine body twisted, legs crumpled, head thrown back, and arms outflung. Splayed upon an altar-shaped pedestal, she becomes a symbolic martyr to humanity’s shared fate. Her youth evokes death’s universality, her nakedness its indifference, and her isolation the loneliness of the final struggle.

Last semester one of the core maxims in my CPS manifesto was “design for emotional resonance.” These pieces really remind me of that power. Honestly, while my current MS2 project can appeal to emotion, I definitely made the decision to put pathos on the backburner this semester – I’m glad I did because I’d like to try out as many different angles as I can while I’m here and figure out what I really stand for as an artist. So far, I think the things I care most about are: emotion, beauty, truth.